Implementing Gotoh

In the previous two posts (1, 2), I introduced sequence alignments for affine gap cost functions and an efficient algorithm to compute them. Here I would like to discuss how to implement it efficiently.

Efficiency can mean different things: First (and this is the usual meaning of it in computer science), it refers to the runtime class of an algorithm, usually denoted using Landau Symbols. This is not what I meant by efficiently here (as we are talking about a fixed algorithm). A second meaning is that the same algorithm can be implemented differently. It still may have the same asymptotic runtime (in the sense of Landau symbols), but the runtime of different implementations of the same algorithm may differ by a huge factor.

When I talk about an efficient implementation, I don’t want to unleash the which programming language is best discussion. Personally, I find this discussion stupid: Efficiency is much more dependent on the choice of the right algorithm and also on the implementation itself, in many cases the choice of the programming language only plays a minor role. When it comes to such a discussion, I always tell the following story:

When I started my PhD, one of my colleagues challenged me with a programming task: He was working on methods for protein structure prediction, and the algorithm of Gotoh is an important tool for many applications in this field. So he wanted to know (a) how much time I needed to implement the algorithm of Gotoh, and (b) how much time my implementation needs to compute some hundred thousand alignments of protein domains. The idea behind that was that we planned to let the students in the advanced practical course implement this algorithm in an efficient way (such that it is applicable to real world problems such as structure prediction), but we did not have a good feeling how much time we should give them for this task.

He already had a Java and a C implementation. His Java version took about 6 minutes for the whole set of alignments, the C implementation finished in 3.5 minutes. Naturally you might say, because C is generally faster than Java. Not quite…

At that time, I already took great interest in efficient programming in Java, and I had read several articles about that already. So, after I had a working implementation, I made a few optimizations and measured the runtime for the set of alignments… 1 minute and 6 seconds!

The lesson here is that, even if it might appear at first glance that the choice of the programming language make a difference in runtime, choices in the implementation itself make an even bigger difference. Importantly, it is not that my colleague’s implementations were particularly bad, he actually is a very skilled programmer. In his defence, he used Gotoh mostly in a more general way (e.g. for profile-profile alignments), and some of my optimizations are only applicable for the special case of predefined substitution matrices.

Correct implememtation

Implementing the algorithm of Gotoh correctly is not as easy as you might think. It is a known fact that Gotoh’s original description of his algorithm was flawed: During backtracking, only the three possible directions were considered, but not from which matrix the value came. It is not difficult to construct counter-examples where this procedure fails.

In the past years of the practical course, we came up with a straight-forward solution to this difficulty. Usually, when you learn about sequence alignment in your basic bioinformatics class, you have to compute an alignment by hand with pen and paper as an exercise. This is of course fine, but because you are lazy and calculating those sums gives you head aches, you do not only tabulate the scores, but also how they were computed (i.e. an arrow to the neighboring cell in the table that led to the maximal value). This seduces people to also store these directions in a computer implementation, and in fact, that is also how Gotoh described his algorithm.

It is however not necessary to store this information, the computer easily can recompute the maximum at each step during backtracking. So this is a trade-off between storage requirement and runtime, you might think, because doing all these computations all over again should cost time, right? However, the opposite is true: It will be faster! The reason for that is, that writing these arrows into a matrix is not free, it costs time. And the computer has to do that for each of the entries. In contrast, backtracking visits entries, so it will be faster for large .

Thus the canonical backtracking would recompute each term in the maximum and continue at the entry producing the greatest value (which is the value in the current cell), thereby hopping between the three matrices. As indicated above this is quite complicated to implement. But there is an easier way: Pretent that you filled the matrix with the algorithm of Waterman, Smith and Beyer (the cubic algorithm for general gap cost functions)! Just inspect , and ; if it is , you know where to continue backtracking; if it is , you know that you have to go left, so just go steps left until and continue with . Guess what you should do if it is …

It is even possible to throw away and (or to implement them using linear space from the first place): If you now that it is not , just check and , then increase and check both again and so on (if you did first the for all k and then for all k, the runtime would increase to ).

Optimizations

A very clean implementation of the matrix filling step looks like this (where s1 and s2 are the two sequences, and subst is a function to access the substitution matrix:

for (int i=1; i<=n; i++) {

for (int j=1; j<=m; j++) {

I[i][j] = max(I[i-1][j]+e, M[i-1][j]+o+e);

D[i][j] = max(D[i][j-1]+e, M[i][j-1]+o+e);

M[i][j] = max(M[i-1][j-1]+subst(s1[i],s2[j]),

max(I[i][j], D[i][j]));

}

}

Most of the computation time is used for quadratic operations, i.e. the contents of the inner loop. It does not matter what you do, all summations and maxima have to be computed somehow, so where is here room for optimization?

Accessing the substitution matrix

One important operation in the inner loop is accessing the substitution matrix. A huge mistake here would be to do a linear search like this:

function subst(c1, c2) {

int index1;

for (; letters[index1]!=c1 && index1<letters.length(); index1++);

int index2;

for (; letters[index2]!=c2 && index2<letters.length(); index2++);

return S[index1][index2];

}

This actually would increase the asymptotic runtime to where is the alphabet. For proteins the alphabet size is 20, which can have a considerable impact on runtime.

I have only heard about an even bigger mistake: Before I even went to university, legend has it that there was a student in the practical course who did the following:

function subst(c1, c2) {

SubstitutionMatrix m = readMatrix(file);

...

}

I hope that it is clear to everyone that it is not a smart idea to read the substitution matrix from file every time it is accessed.

Now let me show you the most frequent solutions of the students in the practical course:

// Variant 1

HashMap<String,Double> S = readMatrix();

double subst(char a, char b) {

return S.get(String.valueOf(new char[] {a,b}));

}

Even if access to the hash table is a constant time operation, creating a char array and computing its hash value are relatively costly operations. In addition, all these char array and String objects must be garbage collected at some point (however, you will probably not even notice that with the Java 8 ParallelGC).

// Variant 2

HashMap<Character,HashMap<Character,Double>> S = readMatrix();

double S(char a, char b) {

return S.get(a).get(b);

}

These nested hash tables avoid creating additional objects, however, Autoboxing and Unboxing produces a considerable overhead here, and, in addition, even if no hash value must be computed, the hash table still has to do several things before it can return the value (e.g. compute a modulo of the hash value).

// Variant 3

double[][] S = readMatrix();

double S(char a, char b) {

return S[a][b];

}

This is much better and possible due to a fact that may not be known to every Java programmer: chars are just unsigned 16 bit numbers and as such can directly by used as array indices.

// Variant 4

int[][] sequences = encode(readSequences());

double[][] S = readMatrix();

double S(int a, int b) {

return S[a][b];

}

There are two potential problems with variant 3: S is relatively large (not only 20x20, but at least 90x90 as Y has ASCII code 89 and is the last amino acid in alphabetical order) and the chars have to be cast to ints (which are the primary type of array indices in Java). For both the impact on runtime is unclear, but of course it is straight-forward to encode all amino acids as ints from 0 through 19.

Switching to integer arithmetic

Every programmer should be aware that computing with integers is much faster than computing with floats (yes, supercomputing guy, I know that the opposite is true for GPUs, but that is not the point here). Unfortunately, you might say, substitution matrices are usually real and not integer.

However, your implementation knows the precision of these numbers beforehand, so it is easy to rescale the whole matrix as well as the gap cost parameters such that everyting is integer. The only thing to do is to rescale the final alignment score. Importantly, noone would give you the substitution matrix with a lot of decimal places, as they are estimated from data which is inherently imprecise.

Initialize matrices once

As said before, the best place for optimization is the inner loop. However, this is not the only place with quadratic operations. When you do a double[][] M = new double[n][m] in Java, the complete matrix is initialized with zeros, which is not for free and a quadratic operation. So, when you have to compute hundred thousands of alignments, it is probably not a good idea to create the three matrices M, I and D every time. As before, in addition to the time for their initialization these matrices will be garbage collected at some time.

Of course, it is not necessary to do that, just identify the longest sequences before you compute any alignment and create the three matrices with the corresponding size. Then you only have to fill in the basic cases in the first row and column once and overwrite the rest for each of the alignments.

Other potential optimizations

There are several other possible optimizations:

- Force the compiler to dereference the outer arrays of the matrices before the inner loop.

- precompute i-1 before the inner loop and j-1 within the inner loop

- precompute o+e

- …

None of these decrease runtime in Java (some even increase it). This is actually not surprising, as some of these optimizations are automatically done by the compiler, and other may have profound implication for the function stack or similar.

Benchmarking the runtime in Java

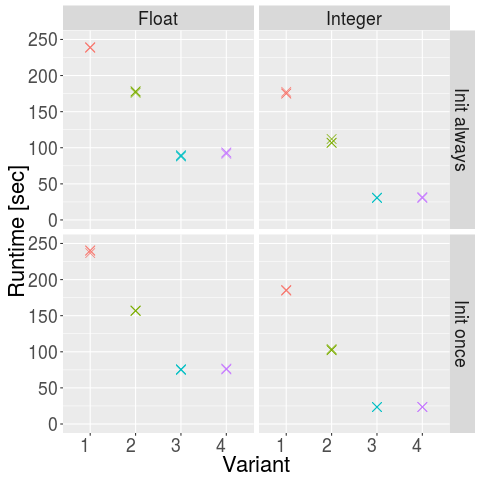

For this blog article, I have implemented the four variants from above to access the substitution matrix, either with or without initializing the matrix for every alignment and either with int or float arithmitics.

I ran the different variants three times on my laptop:

$ uname -srvmo

Linux 4.4.0-45-generic #66-Ubuntu SMP Wed Oct 19 14:12:37 UTC 2016 x86_64 GNU/Linux

$ java -version

java version "1.8.0_111"

Java(TM) SE Runtime Environment (build 1.8.0_111-b14)

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM (build 25.111-b14, mixed mode)

$ lscpu | grep name

Model name: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-5500U CPU @ 2.40GHz

These are the results:

- My laptop is really fast, as it only took 23 seconds instead of more than a minute (or Java 8 is so much faster than Java 6)

- There is no real difference between directly using chars as indices or encoding sequences as integer, the encoding variant even appears to be a bit slower (possibly due to the overhead of the encoding)

- As expected, one hash table is slower than nested hash tables, which in turn is slower than direct array access

- Doing the initialization once helps quite a bit (23.5 instead of 30.8 seconds for integer arithmetic with variant 4)

- Switching from float to integer arithmetic has tremendous impact, reducing runtime from 75.9 seconds to 23.5 seconds (with init once and variant 4)

- The difference from the worst implementation to the best implementation is drastical and makes the difference between going to the machine for a coffee or just having a sip of coffee (just imagine what that means when you for some reason need to compute a hundred or thousand times more alignments!)

Conclusion

Before you start calling Java slow or making any other flimsy argument in favor of your favorite programming language, try to think about better implementations (the programming language may not even matter that much)!